Having Difficult Conversations With Kids

It’s inevitable. At some point, every parent is faced with having a difficult conversation with a child—from the notoriously awkward sex ed talk (remember when you learned about the birds and the bees?) to topics surrounding loss, grief and safety in today’s world. But what do you say when you can’t promise, “Everything will be OK”? There are no magic words, but here are a few pointers for tackling those difficult conversations.

In this article:

Follow your child’s lead in the conversation

When talking to kids about difficult topics, only answer the questions they are asking or else you risk creating more worry. Don’t assume they took in all the details or want to know more. For example, if your child witnessed a car accident, they might ask about the ambulances but not about the people involved.

With older children, you may find they don’t want to talk at first, and that’s OK. Tell them you’re there and available when they are ready to talk. Of course, if you are worried about their safety, be upfront and let them know the conversation is not optional.

Be a good listener

If something frightening happens to your child, or in the world around them, they're probably going to have questions. While addressing a scary topic can be intimidating, conversations about day-to-day issues can be just as challenging. Regardless of the subject matter, it’s important to be a good listener.

- Make eye contact.

- Take the conversation slowly.

- Repeat back what they say without judgment or interpretation.

- Share your empathy.

If your child doesn’t want to talk, don’t push it. Let them know you saw the news (or you heard what their classmate said, etc.), it’s really upsetting and that you’re there if they want to talk about it. On the other hand, if a question catches you off guard, it’s OK to say, “I’m not sure. Let me think about that.” (Just be sure to follow up.)

Acknowledge your child’s feelings

As much as you want to ease your child’s pain, try to avoid comments that might dismiss their feelings, such as “everything will be fine” or “don’t worry about that,” notes Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Strong4Life therapist Jody Baumstein, LCSW. “When a child’s feelings are dismissed, they may think you’re saying their feelings are not OK. In that case, they're not going to share those feelings again. It also doesn’t help reduce their stress,” Baumstein says.

Here are some examples of responding in a way that lets your child feel heard without minimizing their feelings:

- “You’re nervous to go to school because of all the shootings in the news. I can imagine that’s really scary for you.”

- “You got uncomfortable when your classmate made a nasty comment to you. That sounds really upsetting.”

- “I understand that you are sad about not being invited to the birthday party. It is normal to feel sad when we feel left out.”

Why you shouldn’t lie about difficult topics

Your preschooler is worried about bad guys, your middle-schooler is anxious about global warming or your high-schooler is dealing with peer pressure. When you say things like “I will always protect you” or “That will never happen to you,” you are, in a sense, lying. The reality is you don’t know what’s going to happen.

“Lying can cause a lot of damage,” says Baumstein. “Kids are smart. If they don’t think they’re getting the right information from you, they will get the information somewhere else. And a lot of times, it’s going to be better coming from a trusted adult instead of their friends or an internet search.”

Here are a few ways to ease kids’ fears without promising everything will be OK:

- Help your child be present in the moment. For example: “There are no bad guys in the house. We don’t hear any gunshots. We are safe right now.”

- Talk about safety protocols or go over your family plan in case of an emergency to reassure your child knows you take their concerns seriously.

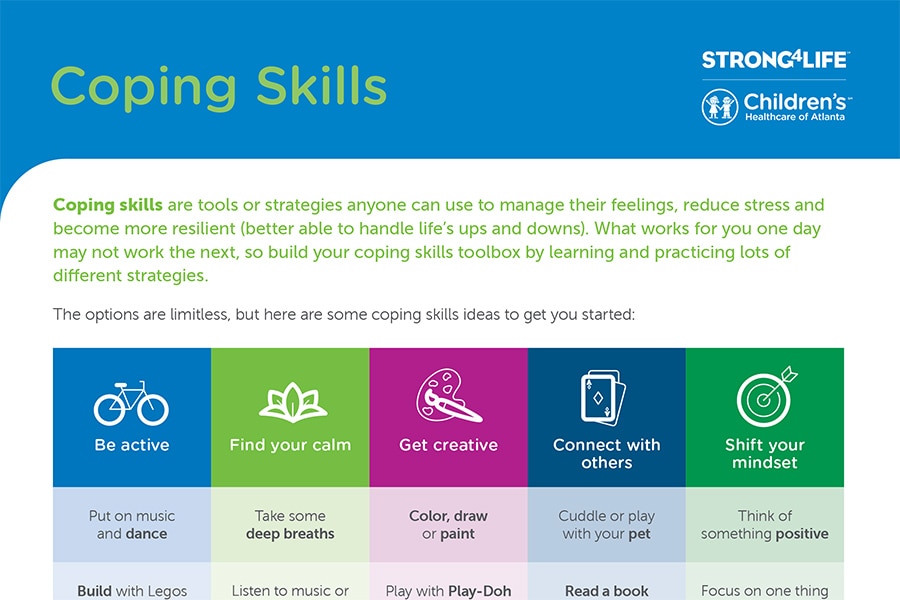

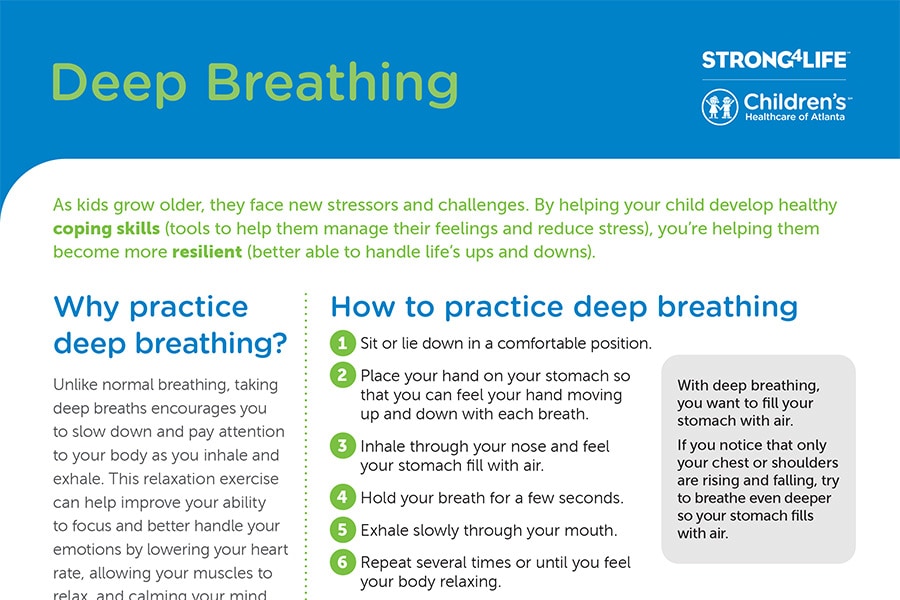

- Teach coping skills, such as grounding your body and mind (focusing on your 5 senses), guided imagery (picturing a relaxing scene), deep breathing, snuggling a friendly pet or writing in a journal.

“There isn’t always a word, or something you can say, that’s going to comfort them,” says Baumstein. “You can say, ‘That makes me uncomfortable, too. I don’t know if that’s going to happen. But right now, we’re OK, so let’s take some deep breaths together and try to calm down and get ready for bed.’”

Download a list of coping skills.

Download a grounding tip sheet.

Download a guided imagery tip sheet.

Download a deep belly breathing tip sheet.

Download a journaling tip sheet.

When to seek professional help

Having a difficult conversation with your child isn’t always enough. If you are concerned about your child or notice any of these signs, it may be time to seek professional help:

- Recurring nightmares

- Frequent meltdowns

- Persistent crying

- Excessive worrying

- A regression in potty training

- Crippling fears (of getting into the car, for example)

- An acute startle reflex (i.e. really jumpy)

Therapy can help even when things are going OK, so don’t hesitate to ask your pediatrician for a behavioral health referral at any time.